In my head, Konkaling was “remote” even for Tibetan standards. If somebody had told me we would be going there this summer - yes, that very place Joseph Rock went to survey for the National Geographic ages ago and at the peril of his life – I would have replied: “No way, not with kids, and not on this trip, maybe some other time.”

But there we were, the whole family driving along to Konkaling described in old travelogues as “holy mountain of the outlaws”, a dangerous, lawless place infested with bandits; a godless area where even the Buddhist monks pillaged, plundered and - hold your breath – murdered!

When I was a little girl, my grandpa would sometimes tell stories about how the infamous Konkalingpas would raid towns and caravans along the old trade routes and how as a child he would hide for days in a monastery or in the mountains fearing for his life.

|

| Konkaling, July 2011 |

When I grew older I discovered books written by early travellers about the area. It became an interesting past-time to sit with my Pola in his room and cross-check what some of them had written in their accounts. He had a hell of a time whenever we talked about it. Often he could confirm points such as the name of a bandit chief or the raid of a specific town. His memory was amazing. He would recall things with such clarity as if they had happened just yesterday. He would even know what this person wore and that the pants were patched or something, down to such detail. Perhaps his memory was so sharp because he couldn’t rely on taking notes: He could neither read nor write as so many in his generation.

|

| Konkaling, July 2011 |

Later I came across more recent publications such as “Khams pa Histories – Visions of People, Place and Authority”, which proved useful in explaining the origins of the communal banditry and lawlessness so prevalent in this corner of Tibet too far for from Lhasa's reach and too wild for the Chinese empire to control. The book outlined “the bigger picture” that helped put my Pola’s stories into a historical context.

He was always surprised at the accuracy in these accounts: What those chigyal (“foreigners”) were doing, what they knew and where they all went. Sometimes, when I summarised a story, he would interject: “Woyah, see? It always comes out! All the sordid details and the negative deeds they committed have now come out for the whole world to see!”

I didn't get it back then. Now as I’m older, I think these “Woyah” reactions were a confirmation of his belief in Ley Gyudrey or the Buddhist law of cause and effect: Even if you got away with your evil deeds in this life, there was no escaping Leydrey, it would take care of everything after all.

|

| Daocheng County (Dabpa), Ganzi Prefecture, July 2011 |

If my grandpa were still around I bet it would blow his mind that I’ve been to Konkaling with his great-grandchildren. I miss the old man for not being around anymore.

Konkaling today is located in the south of the Kardze/Ganzi Prefecture in Dabpa/Daocheng County. Our first stop on the journey was the main monastery of the region, Konka Gompa. Back in the old days, Rock warned against visiting it because its monks were “notorious criminals” who went on looting expeditions between prayer sessions: Dollars to doughnuts that if you were insane enough to come here, they would rob and may even kill you.

But when we showed up almost almost a hundred years later, everything was peaceful. The monastery lay before us in tranquility and solitude. Nobody would ever have guessed its calamitous past from what they saw before them.

|

| Gangkar Namgyel Ling or "Konka Gompa" |

The formal name of the monastery, Gangkar Namgyel Ling had an innocent, quietly soothing, almost angelic ring to my Tibetan ears. The place was idyllic surrounded by lush green forests, and comfortably accessible via a decent road. Two elderly monks were sitting on a bench at the entrance gate with their Trengwa (“rosary”) reciting Mantras and observing the sleepy square.

In the old days, Konka Gompa was reportedly a “co-ed” monastery housing 400 members of the Sangha. But the two elders looking after the site were the only ones we saw. The head Lama or Gondag was Konka Lama, a 12-year old boy residing at his home nearby. Konka monastery also had quite a few monks studying in India, one of the elders said, but he kept his voice low.

To my surprise, a Chinese tour bus showed up out of the blue.

|

| Between Daocheng and Sumdo |

The next moment a bunch of tourists armed with parasols and fans swarmed into the monastery’s courtyard starting to take pictures everywhere. We hurriedly did our rounds inside the prayer hall. Chances were that once that noisy group was inside, it would get difficult to do Chonjay with them walking all over the place and the local Tibetan tour guide in a funny Chupa hurling the names of the various deities into a loudspeaker. You could see this display of irreverence and ignorance in places of worship all the time.

When we were about to leave, several fancy off-roader jeeps drove into monastery complex: More Chinese tourists, this time decked up with high-tech trekking gear. Strange that these people come here, I thought. Were they maybe on some kind of “Lhasa-To-Shanghai” car rally?

Although we weren’t delighted to spot Chinese tourists so deep in Tibetan country, the monasteries reportedly do not dislike them completely. Chinese often “donate” well. They would generously cram notes into the donation boxes you’d find in front of all the statues. Once in a while you could spot some genuinely pious looking people among them as well. Western visitors were perhaps more welcome, but they did not leave a financial impact worth mentioning, and monasteries too had their expenses.

|

| Most of the time roads were in good condition, this section was under construction when we passed |

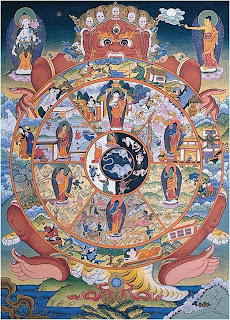

We hit the road before Konka Gompa would become a Chinese circus, driving ever higher into the mountains hoping to catch a glimpse of the three holy peaks that symbolized the Buddhist trinity of Avalokitsvara, Manjushri and Vajrapani. The peaks were considered the guardians of this region. Locals called them Konka Phun Sum (“Three brothers of the White Snow) or Ri Sum Gonpo (“Three Mountains Protectors”).

I still couldn’t believe where I was. It felt like Alice walking through wonderland. I had literally arrived in the place of my childhood stories.

The peaks finally came into sight when we reached the top of the pass where an observation deck had been built that was covered with prayer flags and where we did a Sangsol smoke offering as Mount Avalokitesvara – Chenrezig emerged out of the clouds on the other side of the valley. Below, a small village appeared with a narrow trail leading up the valley to Tsonggo Gompa, a small monastery nestled on the lap of the holy mountain. According to Rock, after each of their raiding trips, the bandits would withdraw to Tsonggo Gompa. Neither the Tibetans nor the Chinese would dare to persecute them.

|

| Nyithen with trail leading to Tsonggo Gompa |

The village in the valley below was Yading, known in connection with “Yading Nature Reserve”, which is listed as a site of UNESCO world network of biosphere reserves Actually Yading itself or Nyithen as was its Tibetan name, turned out to be nothing more than a hamlet with a good road through it. We guessed that they must have taken the name of the hamlet and applied it to the whole region known to old Tibetans as Konkaling and now marketed under “Yading Nature Reserve”.

Historically Nyithen or Yading couldn’t have played a big role. It had to be a recent creation with the nature park. I couldn’t remember having seen the name in old books nor could I remember my grandfather mention the name, nor have I heard of any famous or infamous Tibetans who hailed from “Yading” - Konkaling yes, but not Yading.

Now it was no longer surprising to have encountered a Chinese tour bus at Konka Monastery: Yading was famous in China! Along with Jiuzhaigou/Dzitsa Degu in Sichuan (troubled Ngaba County) and Shangrila in Yunnan (“Gyalthang” in good old Tibetan), it was one of the few Tibetan places apart from Lhasa that received plenty of “domestic” tourists. This is from a Chinese tourist guidebook about Yading we found in a shop in Daocheng:

|

| Every place is a "Shangrila" or a "Shambala" - we may think it's naive, but it works to target the Chinese tourist market |

Surprise, surprise: Just like us, the Chinese tourists also wanted to go up to Tsonggu Gompa. In the old days, no Chinaman, it is said, dared to set a foot onto these lands, and no Tibetan from outside the area either for that matter. But there we were both walking around freely going wherever we wanted - as tourists. And while their ancestors robbed caravans and plundered villages to make a living, the descendants of the historical Konkalingpas now sold overpriced entry-tickets to Chinese tourists and took them on horseback to Tsonggu Gonpa charging them an exorbitant 200 RMB for a 20-minute ride up and down - robbing people the modern way!

I was pretty sure that without the facilitation of Dorje, a friend who hailed from Nyithen and volunteered as our local guide, his fellow Kongkalingpas would have extorted our little group without the slightest Bodrig Punda sentimentalities. We would have had to pay the same exorbitant prices as the Chinese tourists for accessing the Nature Reserve, parking fees, accommodation, food and horse rental. It was every man for himself.

|

| End of the pony trail, from here to Tsonggu Gompa it's on foot even for Chinese tourists |

People seemed somewhat reserved: Not too friendly, not too hospitable which is surprising for a place that lives off tourism. But maybe that’s the general mentality of folks who live rather cloistered lives in the mountains? When we were about to enter Lithang Dzong earlier on the journey, our guide urged us: “When you’re asked where you’re from, just say your grandfather was from Lithang.” - Why? Lithangpas could sometimes be a bit “suspicious”of outsiders, the guide said, and establishing some kind of connection would only help. Well, in Konkaling it was similar. Some kind of connection was indeed helpful.

When walking through the woods up to Tsonggu Gompa, Konkaling reminded me of a Tibetan type “Sherwood Forest” where whoever passes through, has to pay a tribute. Maybe this was an inherited trait from their bandit forefathers and maybe also contemporary, mainstream Chinese culture of everyone-cheating-everyone was rubbing off.

|

| Hiking up to Tsonggo Gompa through "Sherwood Forest" |

The kids had their fun on horseback while we adults, as proper pilgrims, hiked up. I was the slowest in the group taking almost an hour for the short distance: Plenty of time for reflection. If my Pola could see me! He would shake his head in disbelief how times have changed: His granddaughter with her children on an easy-peasy Sunday stroll through a place whose name alone put the fear of god into the people of his generation!

|

| Locals make a living by renting out horses to tourists |

Although it was a foggy and drizzly day in Konkaling when we reached the Tsonggu Gonpa, the surroundings were magnificent. We could have been somewhere in the Rockies. Tibet had so much to offer in terms of experiencing nature. With all the densely forested hills around us, the place would be a symphony of colours in autumn, and in springtime, the meadows would be dotted with flowers and children wearing self-made coronals would run around barefoot.

|

| Tsonggo Gompa, Joseph Rock's "bandit monastery" |

The caretaker monk said the monastery houses around 40 monks with only one or two to be seen. Maybe they were all indoors studying? It was pouring with rain. The caretaker said Tsongo Gompa traditionally had no Gondag or Head Lama. I never knew there was such a thing. I thought every monastery had to be “owned” by some Lama.

The place was clean and tidy. Apart from the absence of a Sangha, which was more the rule than the exception in the monasteries we had seen so far, everything looked in order. The main images in the prayer hall were the Gelugpa trio Je Yabsè Sum. One side-chapel contained images of Dharmapalas, the other contained a large statue of Padmasambhava and Tara.

In the past, I’d never pay attention whether a monastery was this or that. Now in the age of Rimé political correct Buddhism almost the first thing that came to mind, whenever I met someone in robes or visited a new monastery was what Buddhist order they could be connected to.

|

| Konkaling, July 2011 |

So this was the monastery where the lawless bandits used to hide after their raids? If the surrounding rocks could speak! There was no visible trace of the turbulent history of this place. There only was a plate at the entrance of the monastery saying Joseph Rock was here. It was so peaceful and serene up here, for a moment one could forget the political problems Tibet had.

I wondered whether the monks of Tsonggu Gompa knew that a fellow monk up in Tawo in the north of the Prefecture had set himself on fire only a few days earlier. We heard the sad news the day we left our hometown for Konkaling. A monk had told us secretly. We checked the BBC and found the headline but the article itself was blocked.

|

| "Risum Gonpo" on a drizzly, foogy day in July 2011 |

The holy peaks kept hiding behind the clouds. In spite of the rainy weather, the surroundings were exquisitely beautiful. Konkaling was the perfect place for trekking and camping or go on “Kora”. The children would have loved the idea: Hiking around the peaks with pack animals, camp out overnight, eat meals cooked over an open fire and brush teeth on the banks of a clear mountain creek. We knew it was not possible this time, but we had received a foretaste.

Dorje said people were either herding cattle in the higher lying summer pastures, working in the woods or working in a government office in town at this time of the year. But during Saka Dawa everybody would be up here for circumambulation.

I could vividly imagine them racing happily and light-footedly around the peaks in record time.

Once I was on a Kora around Mt. Kailash: Equipped with the best of mountain gear, physically fit and mentally motivated. Still I was regularly overtaken on my walk by old, wrinkle-faced Molas and Polas in cheap Chinese rubber sneakers and thin nylon socks. Not only did they overtake me, their breath was so long they kept reciting Mantras while walking past me. Plus they had enough energy left to give me smile, do the rosary with one hand and turn the prayer wheel with the other. By the time I reached the summit of Dolma-La, the highest elevation of the Kora at 5,500 metres, the Molas and Polas had long been up there drinking tea and chatting. It took me two days to complete the Kora. The old folks finished in one.

Given my Kora history, it would take me weeks to complete the circumambulation around Risum Gonpo. But I knew I would come back here one day on a Saka Dawa and go on Kora around the holy peaks together with the other pilgrims. My Pola would have liked the idea too.

Lhagyelo! – Victory to the Gods!

|

| Wild Iris, Konkaling |

All written content on this blog is coyprighted. Please do not repost entire essays on your websites without seeking my prior written consent.