|

| Students in Chabcha, Qinghai, 2010 |

My partner came home from his latest trip to Tibet a few days ago. He was aware of the Tsongön language protests although he is stationed in another region. He said the governor of his area summoned all educators and warned them not to get involved and spread information about the recent protest especially via SMS. He called for extreme caution because the language protest had become political and he didn’t want people in his area to become associated with it and get (him?) into trouble.

When I listened to my partner, that governor came across as so negative: Instead of displaying solidarity with the demand to keep Tibetan as medium of instruction in classrooms, which is in the interest of all Tibetan-speaking people all over the highlands, this guy specifically instructs people to restrain themselves and keep quiet. What an irresponsible leader! What a miserable coward! No wonder his area figures among the poorest in terms of Tibetan language proficiency. It’s probably not exaggerated if I say the proficiency level among Tibetan officials there doesn’t rise above the vocab of a 5-year old.

I had to think back.

I worked in a middle school there in the mid-1990s. Tibetan wasn’t considered important enough to figure on the curriculum. On my first day in the classroom I was taken aback by the Chinese name cards in front of the students: The children all looked “rugged-faced” but had these names that wouldn’t suit their faces.

“I didn’t come all the way here to teach Chinese kids”, was my first thought, “they tricked me”, was my second thought.

Later when I became friendly with some of the other teachers they assured me my students were all kosher Tibetan kids. They were just not from the surrounding countryside but town kids. By then I had become suspicious myself. During breaks I would occasionally hear snatches of Tibetan when the children were at play.

Gradually I realised that many of those Chinese-sounding names were not properly Chinese after all. For example, there was a boy sitting in the front row with funny glasses. He was a good student. The name on his card said “QI LU RONG”. I figured out “Qi” was his Xing or Chinese family name. It was customary for townspeople in this part of Tibet to have a Chinese family name parallel to their Tibetan family name, that much I knew. Depending on which culture they were operating in, they would use either their Chinese or Tibetan name. Since school is a public affair, the kid naturally used his Xing.

So far so good - but then what was “Lu Rong” supposed to represent? It turned out that was a clumsy Chinese rendering of the local Tibetan, a malapropism of the Tibetan “Lobsang” which in this region is pronounced something like “Luzon”; and since we are dealing with people who are all illiterate in their mother tongue - and since we can hardly expect the Chinese to know the correct rendering of Tibetan names into Hanzi - the bona fide Tibetan name “Lobsang” became the dreadfully sinicised “Lu Rong” - out of sheer ignorance and incompetence.

During that time, I occasionally visited Anye Rinchen, an old Tibetan who had returned from an Indian settlement in the late 1980-ies. When he was a bit drunk he used to tease the local officials: “When you folks go to a conference up in Lhasa, you have to keep your mouths shut because you don’t know Ükè, only the local Tibetan dialect; and when you go to a conference down in Beijing, you folks also have to keep your mouths shut because you don’t know Putonghua, only your local Chinese dialect.” There wasn’t anything the officials could say because it was true. Even Anye Rinchen, himself illiterate in any language, clearly saw their limits.

These are stories over ten years old, Anye Rinchen passed away in the meantime and things have gradually been changing.

My partner said: “The same governor who called for restraint with regard to the Amdo language protests has been taking private Tibetan lessons himself to make up for his deficit.“

“His learning curve must be steep,” I exclaimed, “because a year ago I heard him deliver a formal speech at a new-year event in surprisingly decent Tibetan!”

“Some other intellectually more sophisticated officials must have also recognised their lack in substance”, my partner continued, “Many are taking private Tibetan lessons these days. There is a small presence of Tibetan language teachers from outside the region who cater to those needs.”

Yes, and I also remembered at least one official had a child studying at the Tibetan Children’s Village in Dharamsala although the official version was that the kid was studying in Lhasa.

So when the governor summoned everyone to tell them not to get involved in the Tsongön language protests, was this perhaps intentionally phrased ambiguously so his Chinese superiors would not become suspicious? Was this perhaps not to be interpreted as cowardly after all but as skillful?

|

| Mirig dranyam - keyig rangwang - "All nationalities are equal - freedom of language" |

I asked: “Since the official allegation is that the language protests are politically motivated, what other method than taking to the streets could the students possibly have used? Do you think there would have been a more skillful way for the students to make themselves heard without getting into trouble?”

He said: “It is not clear to me how the government delivered the message and what it exactly entailed. Did they say they want to stop using Tibetan as the medium of instruction? Did they say they want to stop all Tibetan in classrooms? If the message was too harsh, then students and teachers naturally felt threatened.”

He continued: “I am also not sure about the penetration of spoken Tibetan in Amdo. I can only infer it must be a bilingual set-up in the classrooms because the Amdowas speak great Chinese too. I can’t imagine there are exclusively Tibetan-medium schools since education is government job. Still the Tsongön area is way ahead with regard to penetration of the Tibetan language. They teach all the subjects - including the sciences - in Tibetan. Isn’t that wonderful? They continuously develop and enrich our language adding new vocabulary so anything and everything going on in our world and our minds can be expressed in our mother tongue. The work they have done is so encouraging and so important. They have made significant contributions to the continued relevance of Tibetan culture today.”

And then he said something striking:

“When you see how skillful the Tsongön people have been in getting this far within the system – not only preserving but enriching and expanding Tibetan – and when you think of the experience they must possess in dealing with authoritarian government, it’s a bit baffling that they chose to take to the streets rather than looking for a more subtle method. Because they are aware the official reaction to the protests can cause an enormous setback to the advancement of the Tibetan language for a long time to come.”

It’s true. They are risking a lot. We are already hearing of principals, deputies, being fired or transferred and even students being interrogated. And we are learning about more protests. But then should they just have restrained themselves just like this governor suggested?

I said: “It must have been an emotional short circuit. There is no other rational explanation. After all, this piece of news comes just as one more arbitrary policy aimed at pressing the irritatingly non-conform Tibetan identity into the Chinese mainstream. Maybe it was the last straw that broke the camel’s back. Maybe people were just fed up and couldn’t help but to air their anger without thinking about the long-term consequences.”

My partner asked: “Do you really think they have a plan to wipe out Tibetan because it makes us so different?”

I reflected for a moment: “I think it’s not about us and what makes us special. It’s about them and what makes life easier for them. The motivation to press us into the Chinese mainstream is so administering becomes easier for them. It’s all about what is easier and practical for them. They want to lump everyone together so it’s easier for them to manage “the masses”.

My partner reminded me: “But don’t forget, officially they embrace bilingualism. Maybe in practice, it risks to foster separate identities that they want to prevent. So their position on bilingualism in practice becomes ambiguous.”

I said: “Practicing bilingualism correctly also means having to acknowledge people’s diversity, which is contrary to their ill-conceived idea of man. All their policies are rooted in their linear, flat and mistaken idea of man that material well-being is all that people need to be happy. That’s very communist but at the same time it is also very feudal. It’s not like they have problem only with Tibetan, but it goes on to Cantonese and Uighur as we know. “

“I also believe they don’t do a grand analysis of how the Tibetan language – secular or religious – fosters a separate identity,” my partner said slowly, “it’s shallow mind most of the time, I think you’re right. You know they have this word xitonghua, which means to systematize, norm or standardize everything like a commodity. That’s the expression they also use in raising sports figures, athletes. I met one at the airport who said in the West, they focus on the individual’s strength and develop these, whereas in China, they have one single approach for all athletes – “xitonghua”. Since there are so many athletes, chances are out of a hundred, one makes it to the top with this type of grooming.”

“Right, and who cares about the other ninety-nine who failed and whom they’ve messed up in the process? They have more than enough candidates, so who cares about the fall-off?” I replied.

The implications are very clear: There is little space for individuality as far as the government’s dealing with the average Chinese citizen is concerned because that means complicating their work as administrators and organisors. And on this basis we can deduct that there is no space for groups of people either who stick out like the Tibetans or Uighurs or Cantonese speakers because that also means complicating their grand scheme. It’s as linear as that. People face a government in whose mindset they are just a number to be “xitonghua-ed”.

The conversation was helpful because I began to recognize a pattern.

“But now that we’ve figured them out, isn’t it up to us to find ways to work around that pattern,” I asked, “because the way things are at the moment, we do not have power to break it or even challenge it?”

My partner was firm: “We have to challenge them when we believe things go wrong but we have to make sure our actions remain not only peaceful and within the constitution, but at the same time very careful and well thought out. Since their default disposition vis-à-vis the Tibetans is nervousness they are prone to overreact and we have to bear the consequences.”

Then he asked me the crunch question: “Do you think it’s worth making the effort to teach our kids? Do you think they will ever speak Tibetan and use it when they’re grown up?”

We all wonder all along whether it’s worth keeping up the Tibetan identity.

I spontaneously replied: “We have to keep on teaching them and making every effort. It’s the right thing to do. We don’t need to speculate too much about its eventual outcome. We have to do what’s right without getting obsessed.”

I added: “What our children do with their heritage is no longer in our hands and we shouldn’t be too concerned about that either. Also, as people who have faith in the Dharma, we must try to look at this as a practical exercise in the law of cause and condition that says if you create the conditions, you will get matching results. We may not live to see what comes out of this exercise but we can be confident we exhausted all methods that are in our power.”

I don’t know what made me say all that. Life would be a lot easier if we just stopped the Tibetan overtones and became thorough Westerners or Chinese, I’m sure you agree. But when my partner looked at me with what I thought was a warm and loving expression on his face, I knew I had instinctively said the right thing.

It boils down to our demand to respect our individuality versus their habit of lumping everybody together like a commodity and pushing through uniform policies that are easiest for them. It’s a matter of perseverance and individual choice for all Tibetans, whether we live in Tibet or outside. Tibetan spoken at home in the family is where it starts. Even in Tibet with official pressure in the schools, this is completely in our hands and is the absolute minimum we all can do.

Maybe my partner and I are too simple-minded. Maybe we are under-analysing the situation but that’s what we believe. We also believe the accuracy of our analysis doesn’t matter so much as long as we carry on.

|

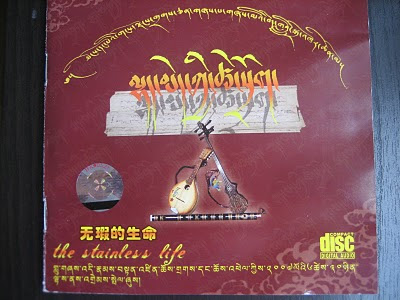

| Kelsang Tenzin Kamè 30 |

I came across a really cool alphabet rap from Tibet the other day. The name of the song is “kamè 30” by a performer called Kelsang Tenzin left in the picture.

Never heard about the guy before, but the song is powerful because it contains an ardent appeal to more self-responsibility in holding high our beautiful Tibetan language.

The chorus says:

Children of the Land of Snows

We Tibetans have a saying:

“No matter how many languages you know

If you forget your father’s tongue, then shame on you!There's a link to the video at the bottom. It’s easy to get distracted by the video because it’s so hip. Just pay attention to the message. It tells us what we need to hear: We can be multi-lingual, widely-travelled, professionally successful, socially respected, politically influential, rich, famous - we can possess all outward signs of success, but if we neglect our mother tongue in the pursuit or fail to pass it on to our children, our achievements are incomplete - because we lost touch with our roots.

There is absolutely nothing to add to that.

Mountain Phoenix

Kelsang Tenzin's "Alphabet Rap"

All written content on this blog is coyprighted. Please do not repost entire essays on your websites without seeking my prior written consent.

All written content on this blog is coyprighted. Please do not repost entire essays on your websites without seeking my prior written consent.